The Brick Oven

If one thing is clear about life for women in rural America during the years leading up to the Industrial Revolution, it is that they were required to have management skills and no where were those skills more important than in the economy of food preservation and preparation. Their use of the brick oven, built into the fireplace masonry, was used in both areas.

To fire/heat up a brick oven, a fire has to be built inside it. This fire, carefully managed by the cook, would heat the bricks to such a degree that the oven could be used for hours – the baking that required the hottest heat being done first. As the temperature dropped, those recipes needing a more moderate temperature were baked. When the oven cooled considerably, it could be used as a “slow cooker” providing enough to heat to cook something over a long period of time, for example, overnight, or as a dehydrator. Squash and fruits prepared in a pulp form could be placed in the oven on trays or plates and gradually dried in the low warmth remaining in the oven. Dehydrating food was one preservation method used to store food stuffs for the winter months.

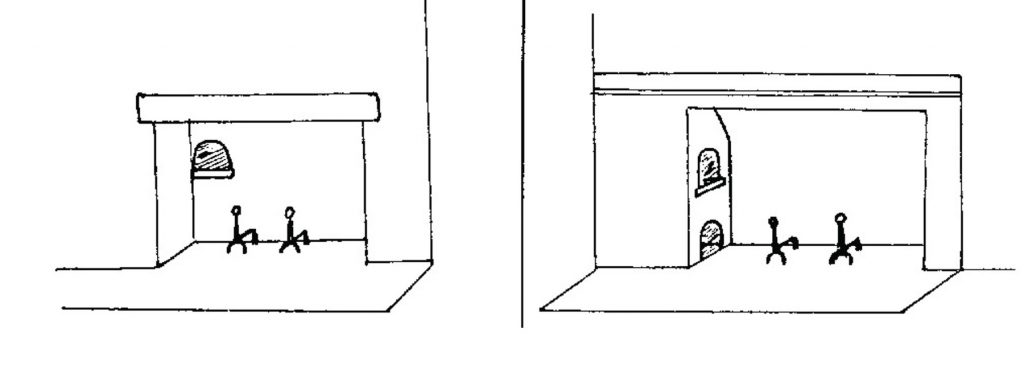

In the early Colonial houses the oven was built into the back wall or a side wall of the fireplace interior.

This allowed the oven to use the hearth chimney as its flue, that is, a separate flue was not necessary to support the fire built in the oven. The position of this oven required the cook to confine the hearth fire in such a way as to allow her access to the oven while keeping her petticoats away from the flames of the hearth fire. Around the middle of the 18th century, fireplace designs started to change. Fireplace openings went from being five or more feet across to four feet or smaller and shallower in depth. The oven moved to the outside wall of the fireplace masonry. By the 19th century, the brick oven was firmly settled on the outside wall. Being “outside” of the fireplace opening itself meant that the oven would require its own flue.

Once the oven was heated and the coals cleaned off the floor of the oven, it was important to keep the heat in. To insure as much heat stayed in as possible a door of either wood or sheet metal was used to close off the opening of the oven from the draft of the chimney or the flue.

By the 19th century, a metal lever was incorporated into the design of the oven opening that when operated would close off the flue. In this case, the door to the oven would be flush with the outside masonry. A good example of this can be seen in the Jailer’s kitchen at the 1811 Old Jail/1838 Jailer’s House.

Among the cook’s skills, woman or man, was knowing how to judge the temperature of the oven. That topic is another article in the future.

Louise Miller, LCHA Education Director

Newsletter

Newsletter Join LCHA

Join LCHA Donate Now

Donate Now